Knowledge mapping

May 8, 2020

By Bryan Leach, P. Eng.

How competitive are your firm’s assets?

Photo ©vegefox.com – stock.adobe.com.

For consulting engineering firms, knowledge assets are a source of competitive advantage in the marketplace. These assets, also known as intellectual capital, include a company’s human capital (i.e. the skill, knowledge and experience of its employees), structural capital (processes, systems and patents) and customer capital (relationships with and knowledge of customers).

Such assets may be rated as core (basic to ‘playing the game’), advanced (making the firm competitively viable) or innovative (enabling the firm to lead in the industry, to the extent it is differentiated from its competitors).

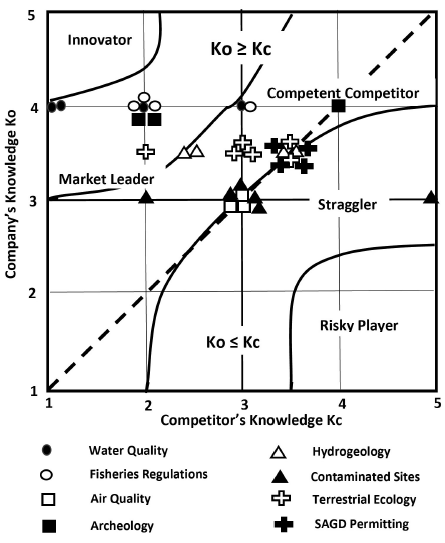

To remain competitive, a firm needs to continually compare the status of its knowledge assets against those of other companies and make any changes as necessary. To do this, the firm must first identify its competitors, then rate both its own and their knowledge assets on the aforementioned scale, awarding one point for core, three for advanced and five for innovative. These ratings help a company to characterize itself within the marketplace relative to its competitors using ‘knowledge mapping’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Image courtesy Bryan Leach.

Going through the process

By way of example, an international consulting engineering and environmental science firm used knowledge mapping as part of a self-assessment process to investigate the competitive status of its knowledge assets within eight technical disciplines in one of its major offices.

Each discipline-specific leader identified three to six of their top competitors and rated their knowledge assets. The average rating of their own assets was 3.56, while that of their competitors’ assets was 2.8. Indeed, with only one exception among 33 comparisons, the leaders rated their assets equal or superior to those of their competitors. All eight disciplines within the office were either competent competitors or market leaders.

The knowledge mapping process stimulated additional thoughts about the firm and its competitors, e.g. “Company X was a five, but their acquisition lowered them to three or four,” “Company Y has a morale problem and is losing good employees,” and “Our own company is untried in these markets.” Another lesson learned was the need to focus knowledge mapping on specific—rather than broad—technical disciplines.

The exercise may also need to be very specific about the type of intellectual capital being considered at each step. For example, a firm may have superior human capital, but inferior customer capital, relative to its competitors, though both types of capital rely heavily on personal relationships between specific individuals in the company and with clients. Such critical knowledge needs to be transferred to the next generation.

Filling the feedback gap

While knowledge mapping can be useful for assessing the competitiveness of a company’s knowledge assets in the marketplace, it is important to note using self-assessment as a method of data acquisition can be flawed, leading to significant differences between perception and reality. Research in the workplace consistently shows self-assessments of knowledge, skills and competence against objective performance are poor, at best, due to the so-called ‘above-average effect.’ That is, people tend to believe themselves to be above average because they lack the information and ability to adequately assess their own competence and that of their competitors.

This gap can be filled by seeking feedback on performance from independent third-party experts, especially clients of the various technical disciplines. Unfortunately, such feedback is often either sought or given infrequently or too late and may be sugar-coated by the client or considered too threatening by the consultant.

Rather than simply e-mailing a customer satisfaction survey, it is preferable to obtain meaningful feedback on performance by having senior personnel conduct face-to-face interviews. By actively conducting post-project audits at their own cost and seeking honest input, a company can also greatly increase its clients’ level of satisfaction with the firm.

Opportunities for change

To remain leaders or to become more competitive in the marketplace, consulting engineering firms need to collect such honest feedback and then use it to assess the status of their own knowledge assets relative to those of their competitors. This is an opportunity to ask some key questions:

- What differentiates the firm within the marketplace?

- Does the firm offer superior human, structural or customer capital?

- Based on this assessment, what does the firm need to do?

By way of example, a firm may choose to integrate, reconfigure, gain or release internal and external knowledge assets.

Integration may involve using existing knowledge assets to develop new products and processes and/or to make strategic decisions regarding the direction of the company.

Reconfiguration may involve transferring knowledge assets across technical and geographic boundaries, developing collaboration networks and realigning assets in response to changes in the marketplace.

‘Gain’ refers to developing new thinking within the company and bringing in new assets through strategic mergers and acquisitions (M&A) or hiring.

Finally, ‘release’ refers to jettisoning those knowledge assets that are no longer required.

In all of these cases, maintaining a competitive advantage requires a company’s leaders and managers to be proactive, rather than reactive, in the management of knowledge assets.

Bryan Leach is a retired Calgary-based engineer who has been designated P.Eng. in Alberta and C.Eng. in the U.K. and now focuses on helping organizations learn. He can be reached at bryleach@telusplanet.net.