The Third Dimension: Today

August 29, 2017

By Andrew Wells, P.Eng., KJA Consultants Inc.

The evolution of vertical mobility includes horizontal travel.

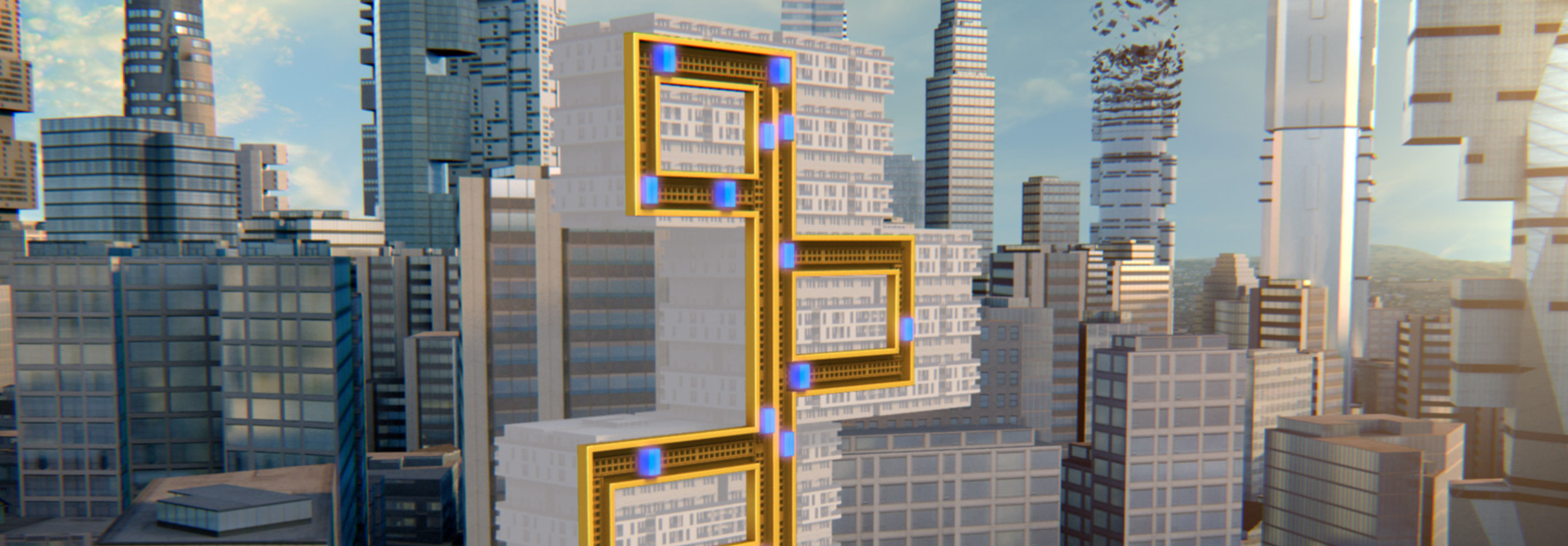

A rendering promoting the new MULTI system from thyssenkrupp Elevator.

In June of this year German-based thyssenkrupp Elevator (TKE) announced the inauguration of the company’s rope-less horizontal-vertical elevator system, MULTI, and their first planned installation project for the new East Side Tower building in Berlin.

TKE’s MULTI represents the latest development with vertical elevating systems that are capable of horizontal movement. The product bears notable similarities and brings to life the concepts described in an industry forecasting article first published on our KJA website’s ‘General Interest’ section which proposes the idea of people-moving ‘pods’ capable of horizontal travel as well as vertical.

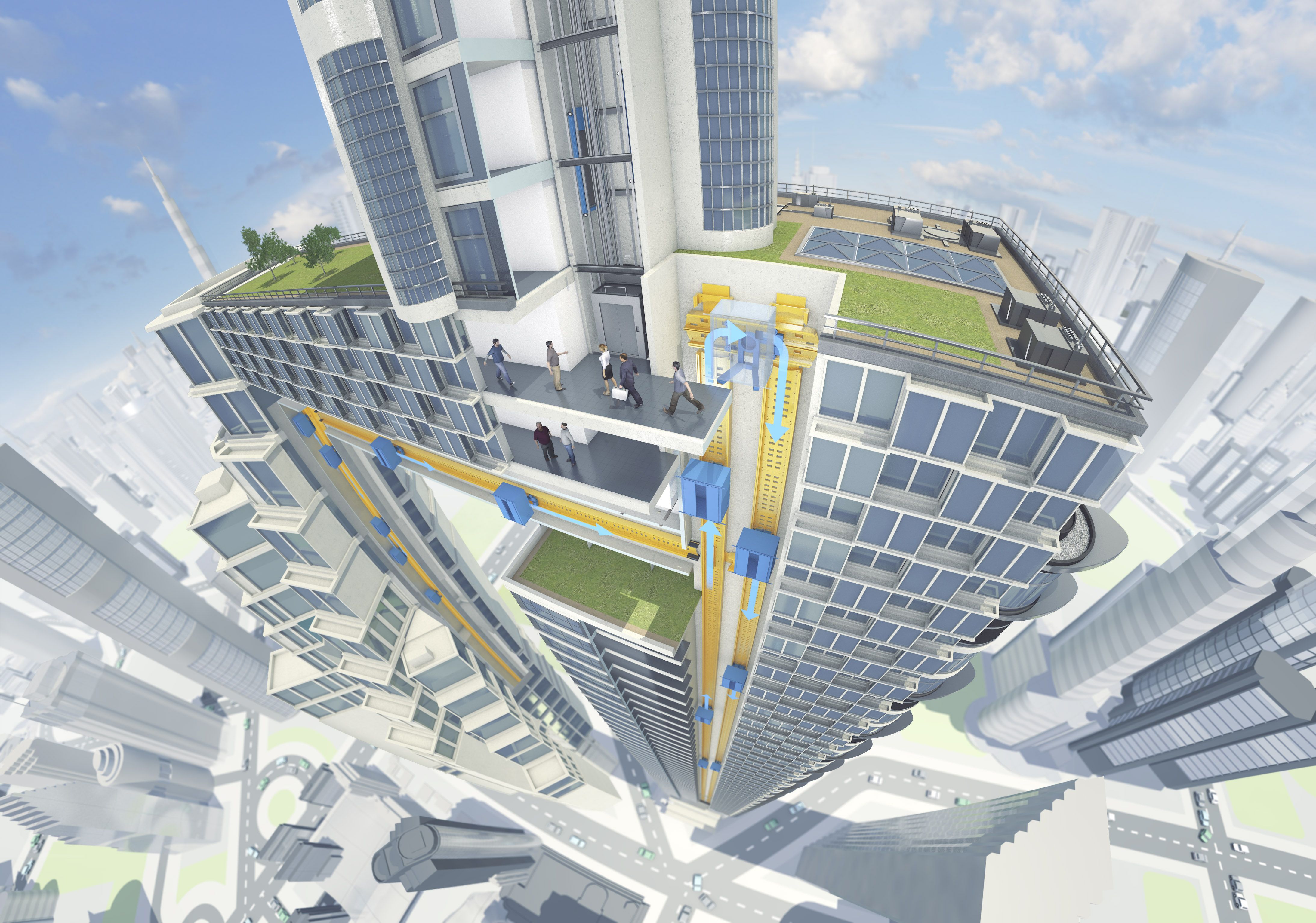

The TKE design makes use of existing technology and new designs to accomplish this feat:

- matching concepts we presented, such as (1) lightweight materials including carbon composites that “…reduce MULTI’s cabin and door weight by up to 50%. …”

- addressing technical challenges we identified in our article with: (2) magnetic levitation (MagLev) lifting forces eliminate energy storage questions and replaces the rack and pinion or traction concepts discussed,

- delivering the mechanism that allows a 90-degree turn in movement needed when a pod changes movement from horizontal to vertical with (3) TKE’s exchange system “…allows the linear drive and guiding equipment to make 90° turns…”

Rope-less

The MagLev technology used by TKE provides the lifting force for the MULTI elevator ‘pods’. Today’s elevators are suspended by steel braided hoist ropes, a construction design that has remained largely unchanged for decades. One can imagine the reaction of early railroad locomotive pioneers if they were to be told that trains in the future would float on a cushion of air, suspended by magnets (intense disbelief would be an understatement). The use of MagLev as a replacement for steel hoist ropes is overdue in our opinion, however, the technology’s cost will be a barrier to mass consumption in the short term.

Early multi-cabin elevator designs

The earliest reciprocating (paternoster) elevators had cabins that moved both up and down inside a building (for readers unfamiliar with the concept, searching pasternoster on YouTube will clarify immediately).

In this design, direction reversal involves brief horizontal movement at the terminal floors and is achieved by suspending the cabins in a continuous loop. For pasternoster design the direction reversals required car doors to be removed leaving elevator passengers exposed to moving hoistway openings at each floor level.

By comparison the MULTI is very similar to a typical modern elevator interior. The design is reported by TKE to have carried a “Focus on Safety” and would be expected to include car doors and entrance protection used commonly today.

In 1997 Otis, a unit of U.S.-based United Technologies Corp., constructed in its North American test tower their Odyssey product. The system enabled “…one elevator car to travel vertically and horizontally through a series of shafts to virtually unlimited heights…” The Odyssey system was never commercialized.

When compared to the paternoster, the modern designs bear no resemblance to their historical counterparts with their use of lightweight composites and state-of-the-art suspension means.

Applications

Applications

In our forecasting article we asked, “What is preventing the industry from immediately manufacturing pods and building new horizontally-vertically integrated complexes?”

Scale is one factor. To develop such a system for a two-floor townhouse would not make much economic sense. To move forward with a new design such as this the building complex would have to be sizeable – probably in the 10 million square-foot range if not larger. Such a complex implies, or demands, government intervention or assistance in a major way.

Consideration of project scale will likely continue to drive decisions as to whether the technology makes sense for a project for many years.

A unique design TKE named as “TWIN” includes two elevators sharing the same hoistway; to date I am aware of 20-30 global installations. Designs such as TKE’s TWIN remain exceptions to the rule in terms of the numbers of running installations globally.

For early adopters a building’s design would center around the use of this technology and would effectively not be replaceable should building ownership, or function, or operating preferences change.

For such a unique installation, the cost of participation will not be the primary factor in choosing to use the technology. Put another way, designing around the MULTI product would happen right from the project’s start, and cost will not be the primary determinant in making that decision.

Competition

Otis’ decision to not release to market their developed product suggests that while interest was present and the concept warranted consideration, Otis did not expect the product to be financially successful.

As a technology’s use continues to increase, so do opportunities for competitors to participate. It is unclear how quickly the product’s adoption might proceed, but given the slow acceptance to date of other unique designs it is not likely to be early. Increased market acceptance will be required to expect to see entry or re-entry by other major manufacturers.

Design Considerations — what to expect?

All product marketing materials are arranged to serve a purpose. Consumers will be well served by conducting independent research to help generate impartial and informed decisions prior to selection.

Often marketing materials do not include or reference supporting data necessary for site-specific analysis. It is not uncommon for performance ranges to be listed with:

- … ‘can increase a building’s useable area by up to’,

- … ‘can increase handling capacity by as much as’ or

- … ‘can reduce power requirements by as much as’.

As with any vertical transportation (VT) system, the passenger movement patterns that are unique to each building need to be studied when considering possible applications.

KJA’s new building design standards require elevators to ‘respond’ in less than 35 to 38 seconds; some of our class-A commercial office building designs deliver average waiting times near 30 seconds.

If a new building was modelled to see the MULTI system responding on average at 30 seconds during the busiest five minutes, this would warrant comparison against what might be expected from a traditional elevator system (at a fraction of the installation cost).

There can be disadvantages to being an early adopter of new technology. The major manufacturers over the years have released products that proved to be problematic.

Should a design prove to deliver operations not meeting expectations, the cost of building retrofits for replacement is high. In an effort to remain impartial on the topic, the designs need not be mentioned, however, they do exist and developers asked would say they are best avoided.

As we look forward into the future and ask when we might be expected to see more mainstream adoption of ropeless horizontal/vertical people pods, it may be helpful to look back into the past.

If we were to suggest in the 1960s to domestic automobile manufacturers that electric or autonomous vehicles could be expected within a few decades, responses would likely be that the concepts seem far-fetched.

It is my opinion that technology, similar to TKE’s MULTI where buildings are designed around VT systems that have more than one elevating device sharing a common hoistway, will become more common within the next 25 to 50 years. cce

Andrew Wells, P.Eng, CEI, EDM-F, SCO(AB), is vp technical services with KJA Consultants Inc., a consulting engineering firm specializing in elevators and escalators.