The challenges of a performance-based building code

December 9, 2022

By Avinash Gupta, P.Eng., Mohamed Mohamed, P.Eng., and Dominic Esposito, P.Eng.

Consulting engineers may face new criteria in design and construction.

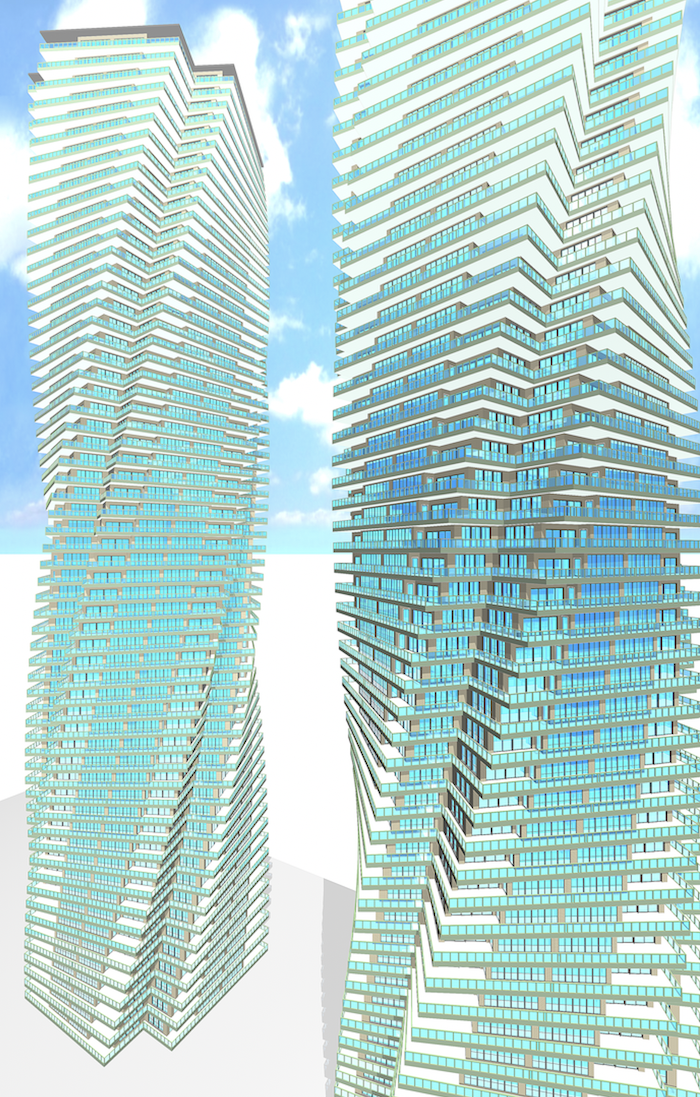

The performance-based building code may be a better option for a high-rise design like this one, which is twisted by the progressive rotation of its floor plates and façade as it gains height, benefiting from a decrease in wind loads and greater energy efficiency as heat gain is reduced. Rendering courtesy Avinash Gupta, P.Eng.

Efforts are in now progress to transition the National Building Code of Canada (NBC) from its primarily prescriptive requirements to a performance-based code with new criteria. This transition poses potential challenges for engineering professionals, particularly with regard to fire and life safety.

From prescriptive to objective-based

Where adopted, all requirements in the NBC must be complied with, either prescriptively or by other means that provide at least the minimum level of performance intended by the code. These requirements are called ‘acceptable solutions.’

The 1995 edition of NBC was replaced in 2005 by an objective-based code, i.e. stipulating overall objectives that were required to be met, with consideration of minimum performance. This code included functional and intent statements to help users understand the reasoning behind the acceptable solutions.

The introduction of the objective-based code was a step toward a performance-based code to enable alternatives to prescribed requirements. Indeed, some of the acceptable solutions in the code are already performance-based, such as Division B: Part 5: Environmental Separation.

With a non-prescriptive approach, the proponent developing an alternative solution assumes responsibility for code compliance and demonstrating such to the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ).

A performance-based approach accommodates greater flexibility in design and material selection.

Seeking flexibility

The performance-based building design concept is not new; in the 18th century, the Code of Hammurabi stated “a house should not collapse and kill anybody.”

The NBC’s current practice is intended to ensure its minimum prescriptive requirements are met in a proposed design, so no modelling or verification tools are needed. In contrast, a performance-based approach accommodates greater flexibility in design and material selection.

In 1982, the International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction (CIB) published “Working with the Performance Approach in Building,’ which explained “the performance approach is, first and foremost, the practice of thinking and working in terms of ends rather than means. It is concerned with what a building or building product is required to do and not with prescribing how it is to be constructed.”

Performance-based design involves understanding the function of the proposed building and its components using resilient, meticulous and consistent scientific tools. All parts of a building must be subjected to scrutiny when developing a performance-based design.

While prescriptive requirements are embedded in the NBC and, thus, easier to deal with than performance-based requirements, they may not be the most desirable and economical solutions. Performance-based approaches may employ better, more innovative or cheaper solutions without compromising quality and safety.

That said, prescriptive specifications will continue to play a significant role, as adequate knowledge for some performance features is not available. Specifications will often need to be expressed partly in performance terms and partly prescriptively.

Other motivations for retaining prescriptive requirements include the cost of a performance evaluation of a product in comparison to its price, a scarcity of professional resources, skilled labour and contractors or the absence of a local construction industry to build complex performance-based designs in remote parts of Canada.

Further, significant effort is required to design a performance-based building with adequate safety for occupants and property protection. The design should state the level of performance projected from experiments, calculations or modelling.

The introduction of the objective-based code was a step toward a performance-based code to enable alternatives to prescribed requirements.

Preparer and reviewer qualifications

The qualifications, training and experience required for designers who develop performance-based buildings are not explicitly specified anywhere; there is no formal certification or educational training program. A registered and licensed professional engineer may create performance-based designs until provinces and territories determine such qualifications.

In the meantime, the AHJ plays a pivotal role in assessing the methodology and levels of safety for developing a performance-based design. The qualification, training and experience of AHJs are key in approving performance-based designs.

Performance criteria

The Society of Fire Protection Engineers (SFPE) Handbook provides a framework of performance criteria for an agreeable level of risk to a building’s occupants. One of these criteria, for example, is the safe evacuation of occupants before the environment becomes untenable in a fire emergency.

For a performance-based design, the team chooses fire safety criteria in consultation with the AHJ, based on the overall intended performance of an adopted code or standard. The fundamental prescriptive requirements will still constitute part of the design.

The AHJ plays a pivotal role in assessing safety for a performance-based design.

Application of performance-based design

The performance-based design approach provides flexibility, but does not and cannot replace the current model code. Consider the following example.

A 50-storey building is proposed with 500 occupants on the uppermost floor, which features an observatory and a nightclub. Located 150 to 160 m above grade, the most apparent concern is safe evacuation.

The NBC requires at least two remotely located exits, adequately sized to serve the occupant load, clearly visible, identifiable and always accessible. The building’s height and occupant load suggest compliance with NBC provisions would require many more—or wider—exit stairs from the uppermost floor to grade level. Complying with the code’s acceptable solutions is not only a challenge, but may be impractical. So, a performance-based design is a better approach.

The building could be designed with refuge floors, where all occupants of the uppermost floor would be moved before they are evacuated. Another or complementary solution may be to specify high-speed elevators with additional fire and life safety features, although the risk of these elevators being out of order must be considered in the evacuation strategy. Available safe egress time (ASET) and required safe egress time (RSET) are essential to assess any fire scenario.

So, performance-based design might be practical for a structure that, due to its configuration, cannot technically meet existing prescriptive requirements. The designer must meet a predetermined set of performance criteria complementing the fundamental code provisions.

The main areas where performance-based design and procurement could be considered are service engineering, energy consumption, lighting, plumbing, air quality and heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC).

One significant challenge is how to predict performance.

Addressing concerns

An immediate concern is the role of the AHJ in reviewing and approving a performance-based design proposal. Currently, most jurisdictions hire building officials who must pass all the code exams or are professional engineers, but may not be qualified to validate time-based egress analysis and/or smoke modelling, both of which are commonly required for managing a fire and life safety performance-based design.

Another significant challenge is how to predict performance. This will become feasible by developing educational modules for design professionals that show where, why and how the performance-based building concept is already being put into practice, with examples and explanatory notes. In the long term, a mandatory semester on performance-based design could be included in the curriculum for engineering schools.

In the meantime, it is of utmost importance to discuss a performance-based design for any project with the AHJ before committing, as many municipalities do not entertain alternative solutions. Reliable documentation must be negotiated and agreed upon between design professionals and regulators at a conspicuous location; such information will be essential to any forensic team investigating the reasons for a failure in the future.

Avinash Gupta, P.Eng., is chief code compliance engineer and assistant fire marshal for the government of the Northwest Territories. Mohamed S. Mohamed, P.Eng., is East Canada manager for Jensen Hughes. Dominic Esposito, P.Eng., is a senior project consultant for Jensen Hughes. For more information, contact Gupta at avinashguptap.eng@gmail.com.