The adventures of an engineer in the early 1900s

January 27, 2022

By Brian Lott

An immigrant’s early career ushered him across Canada.

The recently published book of memoirs, Emigration and the Adventures of a Young Engineer in Canada (1907-1914), provides a vivid description of my father’s life in Canada before the First World War. Harry Chickall Lott earned his diploma in engineering at Central Technical College in London, England, and worked for a consulting engineering firm, whereby he first saw Canada during a 1905 Atlantic cable laying expedition. He decided to immigrate there in 1907 at the age of 24, arriving in Montreal with £10 in his pocket and no job. He was introduced to Milton Hersey, a consulting mining engineer who had set up a mineral testing laboratory in Montreal.

The following is assembled from excerpts from the book:

“Hersey gave me a letter of introduction to Mr. Kenny of Allis Chalmers Bullock, electrical plant manufacturers, and I was told to turn up on Monday morning for an interview. Needing an income immediately, I accepted their offer of only 15 cents an hour; and so, seven days after my arrival, I was working in Rockfield in their high-tension testing department. I was a graduate with two years of practical experience, but unskilled labourers digging foundations outside were paid considerably more!

“With only 24 hours’ notice, I would head to a new job in another province.”

After six weeks, I had an offer of a job in Sydney, N.S., with the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company at $100 a month. I used this offer to look around for a more suitable post and was offered—and accepted with outward hesitation but inward alacrity—a job at $75 a month as an inspector with the Canadian Inspection Company of Montreal. My work involved inspecting steelwork and tapping thousands of rivets at the Dominion Bridge Company in Lachine, Que., sampling cement and testing cables and telephone wires.

Harry Chickall Lott inspected Winnipeg’s Redwood Avenue bridge while working for the Dominion Bridge Company.

In August 1908, I was told to leave by the evening train for Winnipeg, where I was to work as an inspector of the Redwood Avenue bridge. I went to the Dominion Bridge Company to pick up the drawings and was given final instructions with a letter of introduction to Col. Henry Norlande Ruttan, the city of Winnipeg’s chief engineer, to whom I was to report. Before leaving Montreal, I spent a couple of evenings in the library of the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering (CSCE) studying the theory of bridge design and especially swing span bridges, so I was well-prepared.

Within hours of arrival in Winnipeg, I had reported to Wilson, Ruttan’s assistant chief engineer, met E.E. Shephard of the Dominion Bridge Company and started my inspection of the bridge, a through-truss steel road bridge which had an electrically operated central swing span and crossed the Red River at Redwood Avenue.

The erection of the bridge went well and the swing span was in place by Christmas. On Jan. 5, 1909, an unexpected telegram from my head office read ‘Leave today if possible for Toronto.’ So, once again with only 24 hours’ notice, I left the next day for a new job in another province.

The 1,230-mile train journey to Toronto took 47 hours. It was relaxing and enjoyable and, like my earlier journeys, provided me with the only holidays I had during my first 18 months in Canada.

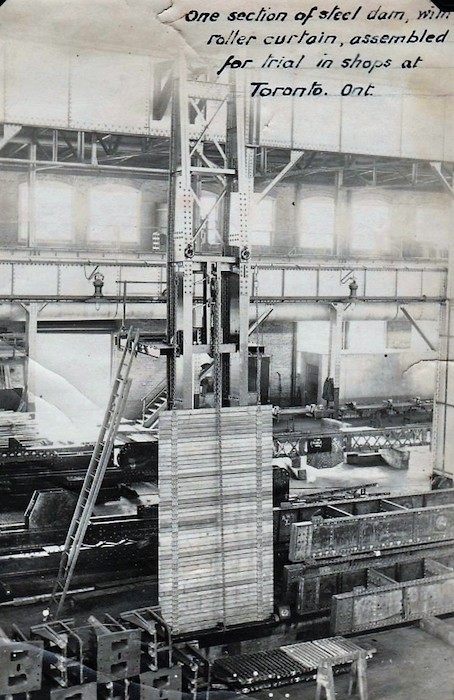

Lott resigned from the Canada Foundry Company in Toronto while working on Winnipeg’s challenging St. Andrew’s Dam.

My job in Toronto was chief inspector for the manufacture, in the workshops of the Canada Foundry Company, of a bridge and movable dam to be erected across the Red River below Winnipeg at the St Andrew’s Rapids, for the Government of Canada. The total weight of steelwork and machinery was about 3,000 tons and the government specifications were extremely severe. The Caméré curtain design of the dam was unique on the American continent and was copied, far too slavishly, from a dam in France. The difficulty of getting the extreme accuracy demanded by the specification resulted in almost continuous trouble for me with the Canada Foundry engineers and I came under fire from my boss. My position became so difficult that I decided to resign after a measly pay increase of $5 to $90 per month.

“I studied the theory of bridge design and, especially, swing span bridges.”

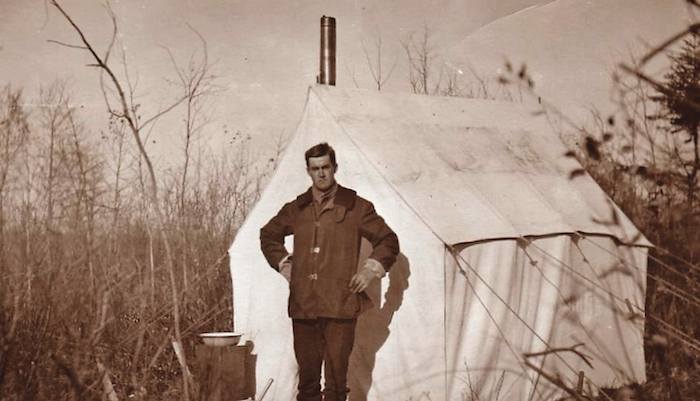

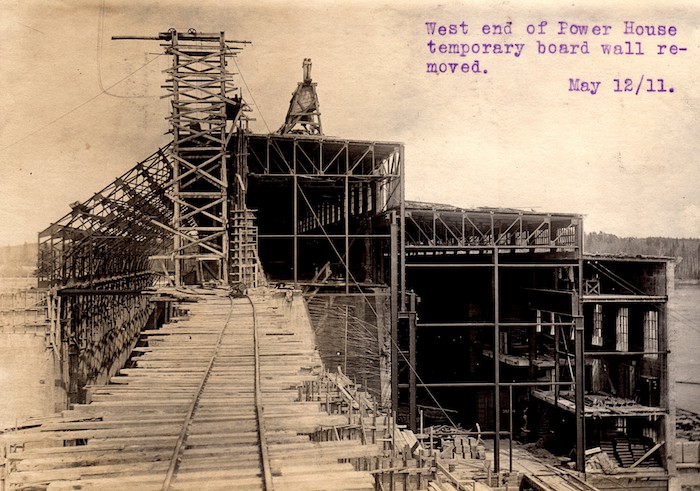

After a three-month visit to England during the summer of 1909, I returned to Winnipeg, where W.G. Chace of Smith, Kerry & Chace, consulting engineers, offered me a job as an inspector in the field at $75 per month, with accommodation in a tented camp, on the construction of the 77-mile long, 66-kV electricity transmission line from Winnipeg to the city’s hydroelectric plant being built at Pointe du Bois.

The design and construction of the transmission line and powerhouse followed, as well as life in the construction camps, summer and winter, for two years, interspersed with canoe trips and moose hunts and visits to civilization in Winnipeg.

Lott also worked for Smith, Kerry & Chace as an inspector during the construction of a 77-mile long electricity transmission line from Winnipeg to the Pointe du Bois powerhouse (pictured).

During one such visit to discuss the completion of the transmission line with Chace, he said he wanted me to leave that evening for a week or two in Prince Albert. With only my city clothes in my baggage, I left on the Grand Trunk Pacific (GTP) train, arriving in Prince Albert the following afternoon. My job was to witness some test boring in the bed of the North Saskatchewan River to find a good foundation for a dam to serve a new hydroelectric scheme for the city. The ‘week or two’ turned out to be almost three months.

To obtain cores from the riverbed, the drillers had a large scow (80 by 28 ft), on which was mounted a steam boiler, engine and drilling gear. Several weeks’ drilling gave no hope of a suitable site for a dam and so, after spending two months on the project, my firm withdrew their support and my services for this ill-conceived project.

Instead, we recommended that the city build an extension to their existing steam power plant. Our recommendation was ignored and the Prince Albert engineers, together with their Toronto consultants, continued with the construction of a dam at La Colle Falls for a further two years, eventually spending $3 million before the scheme was abandoned, nearly bankrupting the city.”

His story continues in the book. To order a copy, visit Amazon.

Brian Lott is an engineer in the U.K. who has published his father’s memoirs. For more information, contact him via email at lottb@imcgroup.co.uk.