Engineering for global warming and climate change

June 23, 2022

By Stan Ridley, BSc(Hon)Eng, MSc(Eng), DIC, C.Eng., MICE

There are hydrotechnical aspects to consider.

The global warming and climate change (GW&CC) crisis is profoundly affecting the meteorology, precipitation and hydrology in many parts of the planet. In British Columbia, hydrotechnical and engineering aspects and issues, mainly related to our rapidly changing climate, have been very evident over the last few years and were particularly so in 2021.

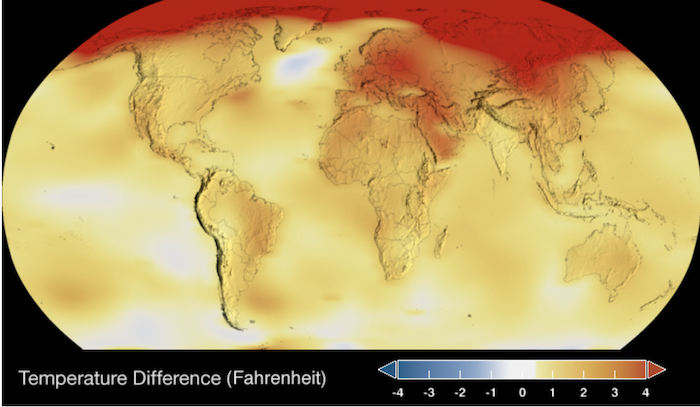

Possibly because of the high temperature increases and resulting rapid melting of the Arctic, we in Canada seem to be experiencing a sobering preview of extreme climate changes that will surely touch most parts of the planet. The NASA figure below needs no explanation and the U.K. and Europe also look awfully warm when compared to the 1884 global ambient temperature base.

In B.C. our weather has been changing relatively fast and in 2021 we experienced an extreme heatwave (e.g. 49.6 C, 121 F. in Lytton) and massive flooding in November 2021.

As a result of the changing climate and particularly precipitation in B.C., the weather patterns are changing rapidly, probably “for the wetter” in the autumn and winter and “for the dryer” in the summer. As a result, it will be necessary to reassess our hydrotechnical design basis standards for both major existing infrastructure and for proposed facilities.

Of course, GW&CC are not the only phenomena affecting our climate, meteorology and hydrology. In B.C., the logging of significant areas of our massive forests and industrial, commercial and residential developments have, over many decades, incrementally contributed to the rate and magnitude of runoff and changes in topographic drainage profiles. However, recent flooding and other climate changes have not been “incremental” but extreme, as noted above.

As an example of infrastructure of major importance are our hydroelectric facilities with their > 60 dams, > 30 hydroelectric facilities and associated reservoirs, spillways, power plants (about 16,000 MW, 55,000 GWh/year) and reservoir landslide areas (https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/energy-markets/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles/provincial-territorial-energy-profiles-british-columbia.html).

B.C. Hydro, which owns and operates most of the major hydroelectric facilities in the province, operates a substantial dam safety program that reassesses, on an ongoing basis, the hydrological and seismological safety and stability of their major structures and systems, including the spillways and major landslide structures above the large reservoirs (e.g. https://docplayer.net/120262234-Landslide-risk-management-at-bc-hydro-experience-with-landslide-monitoring-and-drain-age.html).

For high-risk dams, the meteorological and hydrotechnical analyses and assessments require the estimation of the probable maximum precipitation (PMP) and the probable maximum flood (PMF) inflows for each major reservoir.

The PMF is the flood that can be expected from the most severe combination of critical meteorological and hydrological conditions that are reasonably possible over and in the drainage basin under study. This PMF is the estimated upper limit for determining the inflow design flood (IDF) that includes inflows from the PMP.

For less critical structures, most of Canada’s hydrotechnical design standards were developed on a probabilistic basis of up to about 1:1,000 annual probability, based on historical records of typically less than 100 years. However, with the rapidly changing climate, these historical records may not be relevant going forward. However, for major high-risk structures, like the spillways of major reservoirs and dams, deterministic/maximization models are typically used to calculate the PMF design inflows. These analytical models attempt to maximize weather/storm systems over the subject catchment basin and the antecedent snow pack and soil moisture content, the latter to minimize the runoff concentration time for each drop of rain (and/or melting ice and snow) to flow into the river/reservoir.

“Back calculating” the PMFs so obtained, using probabilistic analyses and based on the extrapolation of relatively short historical records of river flows, can result in very long estimated return periods like 1:10,000 to 1:100,000 annual probabilities with quite a lot of sensitivity “scatter” within the jaws of analytic uncertainty.

However, today, with rapidly progressing GW&CC, our historical records may not be relevant and reassessments, relying on past meteorological and hydrological records, seem less than relevant.

The photo above shows a test of the Revelstoke spillway passing a small % of the PMF, i.e. the two gates only slightly opened. Passing the full design PMF down that spillway would be quite a spectacular event.

Of course, the point is that so much of our major infrastructure, both existing and future, depends on reliable climatological and hydrotechnical data and analyses. Many of these facilities will need to be checked and possibly reconfigured to accommodate our changing climate and resulting meteorological and hydro- logical conditions, but using what input data?

The recent major November 2021 floods in B.C. caused extraordinary damage to our infrastructure, particularly our highways, that cut-off and restricted access for goods and services across the province for many weeks.

The meteorological and hydrotechnical specialists surely have their “work cut out,” re: the recalculation of realistic major floods with up to 1:1,000 annual probabilities and also the much larger deterministic PMFs for high-risk structures.

Meteorological and hydrotechnical aspects of our changing climate are not the only GW&CC adaptation challenges. With a tornado/waterspout forming off of Vancouver International Airport on Nov. 6, 2021, there are other design standards that we will need to reassess.

In Canada, both federally and provincially, we have strong protocols in place to regularly reassess our engineering standards. The call to action suggested by this brief article is to try to come to grips with the reality that we seem to be facing major changes in our climate systems. While we need to take action now to re-assess the relevant design standards, the big question is on what basis?

Stan Ridley is president of West 2012 Energy Management and a member of the United Nations ECE Groups of Experts on Gas and on Coal Mine Methane. He is based in Vancouver.